Searching for information online

Learn how and where to search for information online for research-based assessments; analyse a topic and develop a search strategy.

Information sources and types

Sources

Information can be found in a variety of sources and each source contains different types of information.

Sources include:

- Journals

- Books

- Digital encyclopedias

- Audiovisual material

- Web pages

Types of information found in sources

Information contained within a book may have taken years to compile. The book must then be accepted for publication, before printing and sale to bookshops and libraries. As a result, information in books tends to be less current than information found in other sources, such as journal and newspaper articles.

Some, if not all, of the book’s contents (or chapters) may be relevant to your research, providing a good, general background to your topic.

Academic journal articles contain original research, written by subject experts, and these have been ‘peer-reviewed’ i.e. reviewed by other experts, before publication.

An article from an academic journal such as Social Work Review, will also include an abstract and a list of references or other readings.

The target audience for this information includes subject specialists, academics and scholars.

Articles in popular magazines, such as More and Sports Illustrated are primarily written to entertain, rather than educate and inform.

A typical magazine article will relate to contemporary events, and be written by someone with general, rather than expert knowledge of the subject. Magazine articles are generally easy to read and accompanied by glossy photos and advertising.

Newspaper articles are written by journalists and primarily aim to inform the public about current news and events. They are typically short in length and ‘currency’ is very important.

Articles in newspapers include news reports, opinions and reviews, and local interest stories. Newspapers are generally produced daily, or weekly.

Government bodies, committees or project teams produce government reports.

Generally, the group considers some specific issue, such as the ‘wellbeing of children in New Zealand’ and reports findings and makes recommendations. Information in these documents comes from a variety of informed sources, including subject professionals, academics and other interested parties.

Primary sources of information include anything that is original such as:

• Original research

• Reports of an event recorded by someone who was there

• Personal memoirs, diaries and autobiographies

• Interviews

• Statistics

• Photographs

Secondary information sources interpret, analyse or describe primary sources and events – they are at least ‘one step away’ from the actual event.

Many books and articles contain secondary information, including text books and scholarly reviews.

Search terms

The first step to finding information is to develop a search strategy. A search strategy determines what, how and where you are going to search for information.

Developing a search strategy involves:

- Choosing the best search terms for your topic

- Using appropriate search techniques

- Identifying the best search tools to use

Search terms are the keywords and phrases that you use to search for information. They consist of the words which describe the main ideas of your research topic.

Your initial search terms can be found in your research topic. This initial list is then developed.

Activity

Identify the initial search terms from the topic sentence: What impact has New Zealand’s nuclear free policy had on its foreign relations?

Start

Developing your list of search terms

Add other words that also describe the research topic to your list of search terms, including:

- Synonyms (e.g. anti-nuclear)

- Abbreviations (e.g. NZ)

- Related words (e.g. Greenpeace)

List these other words under the original search terms that they relate to. Make an additional list of any other ‘useful terms’ that could be relevant.

Developing search terms activity

Identify the synonyms, abbreviations, and related words to the original search terms extracted from the topic sentence.

Start

Tips to remember

-

Computers don’t think in words or the meanings of words, they just search for sequences of characters.

-

Use subject-specific terms when researching. For example: 'child development' rather than 'growing up'.

-

Avoid phrases that are not likely to be actually written in the resource. Such phrases would include “documentation on”, “pages about” or “discussion on”.

Search techniques

Using search techniques appropriately will enable you to successfully find information online.

Basic search techniques include:

-

Keyword searching

-

Phrase searching

-

Boolean searching (using AND, OR, NOT)

Keyword searching

Keyword searching is a technique that searches for your search term anywhere.

Effect of keyword searching on your results

Keyword searching can increase the number of search results. It is a very general search - not all of the results found may be relevant to your topic.

For example, a keyword search on the term "New Zealand" will find items on many different topics.

Phrase searching

Phrase searching narrows the search to retrieve only those results that contain that exact phrase. It can also increase the relevancy of your results.

Place quotation marks around the search term eg: “nuclear free”.

These are some relevant search phrases related to the topic: nuclear free

| Anti-nuclear | ANZUS treaty |

| Nuclear testing | Rainbow Warrior |

Boolean searching

Boolean searching is a technique that connects search terms using AND, OR, NOT. Note: these terms must be in capital letters.

-

AND

Search results will contain both search terms

“New Zealand” AND “nuclear free”

-

OR

Search results will contain at least one of the search terms.

“nuclear free” OR “anti-nuclear" OR “no nukes”

Note: OR will increase the number of possible results but they may not all be relevant.

-

NOT

Search results will exclude a term after NOT

“nuclear power” NOT “nuclear weapon”

-

Brackets ( )

Use brackets to group search terms together when using combinations of AND, OR, NOT.

“New Zealand” AND (“nuclear free” OR “anti-nuclear”) NOT “nuclear weapon”

This will find information relating to New Zealand and the idea of nuclear free or anti-nuclear. It will not include any information relating to nuclear weapons.

Where to search

Places to search for information online include:

-

Library catalogues

-

Databases

-

Subject guides

-

The Internet

- Google Scholar

Library catalogues

Library catalogues, like Library Search | Ketu at the Robertson Library, provide information about the items (e.g. books, journals, media, newspapers) that are held by the library. The kind of information found on a catalogue includes:

| Description of the item e.g. author, title, publisher details, subject links and sometimes the contents page |

| Location details e.g. call number, collection, and name of the library |

| Links to electronic resources e.g. e-journals, e-books and some websites |

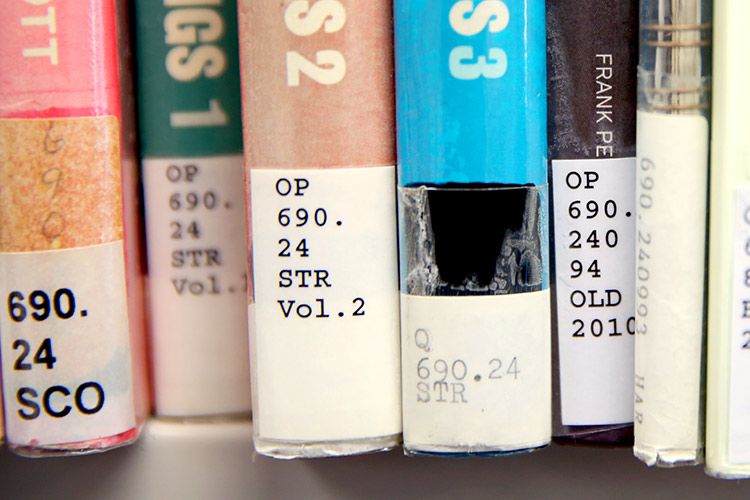

Call numbers

The call number in the library catalogue tells you where to find an item. It gives the library branch, collection and classification.

Each item (book, journal, microfilm, video) has a unique call number made up of letters and numbers.

Each item has a unique call number made up of letters and numbers. The Robertson Library main collection uses the Dewey Decimal system.

Databases

The term 'database' usually refers to an online search tool that indexes collections of information. Many of these databases are subscription-only – e.g. ProQuest Central - and libraries pay to get access on your behalf. Some of them are freely available – e.g. PubMed. Most library websites will provide links to both the databases they subscribe to as well as the freely available ones.

Databases vs the Internet: Why use library databases at all?

If you search Google, you’ll find plenty of results related to your search topic, but how do you know whether those sources of information are reliable?

Databases link you to information that has been assessed as reliable, and give you easy options for narrowing your results to relevant research-based material (academic, scholarly or peer reviewed sources). If you are using the Internet, there are ways to evaluate online information.

Library databases are most often used to search for:

-

Journal articles (popular and academic)

-

Newspaper articles

-

Book reviews

-

Conference papers

-

Dissertations and theses

Information found on library databases includes:

-

Citation information – e.g. article title, author, journal title, volume, issue, page numbers

-

Abstract – summary of the article

-

Full text – full text of the article

-

PDF – scanned image of the full text of the article

Tip

Not every item you find in a database will be able to be accessed in either full text or as a PDF. If the database name includes the term Index, you probably won’t get full text access to the results of your search. You’ll find the same situation with freely-available databases, such as PubMed, as publisher’s charge quite a lot for access to research articles.

The content of a database can be arranged by:

| Geographic location e.g. Index New Zealand contains New Zealand information |

| Subject e.g. Pubmed contains medical information |

| Multidisciplinary e.g. ProQuest contains information on a range of geographic locations and subjects |

Subject Guides

Subject guides point you to the books, journals and databases to support your studies in a particular subject area or programme. Some resources will be available online and others are available at the Library.

Subject guides also provide guidelines on how to find more information in the area you are looking.

The Internet

Although library resources and databases have already been pre-screened and evaluated, anyone can create a web site. There is no automatic pre-screening or fact checking of web sites so evaluate each website you read before you use it for your academic research.

Search engines

Search engines are tools to help you search for websites. No search engine covers the entire web, they all have different ways of searching, so it's a good idea to use more than one search engine to search thoroughly. Google is one of the largest and most popular search engines. It is a good place to start your search.

Other search engines include:

Google search tips

Search within a page

You can also locate a specific word or phrase on a page by searching using the find tool.

The find tool is usually located in the tool bar of a web browser or you can also use the keyboard shortcuts Ctrl+F (Windows, Linux, and Chrome OS) and ⌘-F (Mac) to quickly open the find bar. The search terms will be highlighted where they appear on the web page.

Tip

You can use this tool on any page, in any browser or document.

Advanced search operators

Use these search operators to limit the areas where the search terms are found.

The search term must be contained in the URL.

For example: inurl:AIDS “health care” means you are searching for websites with the term AIDS as part of their web addresses and health care written in the text of the pages.

The search term must be in the site address of the web page.

For example: insite:ac.nz “commercial architecture” will find web pages of New Zealand educational institutions with the phrase commercial architecture in the text of the page.

insite:-.com pneumonia will find all pages that are not .com (that is commercial or individual owned) and will only show pages with pneumonia in the text and .org or .asn or .ac or .gov.

Finds words in the title of a page.

For example: intitle:“hybrid cars” “fuel consumption” will find pages which have the phrase hybrid cars in the title of the page and the phrase fuel consumption in the text.

Finds all the words in the title of a page.

For example: allintitle:“hybrid cars” “fuel consumption” will only show pages that have both phrases in the title of the page.

Looks for web pages with a particular file type.

For example: “New Zealand Government” filetype:ppt will produce pages which are PowerPoint presentations with the phrase New Zealand Government in the text.

intitle:indigenous policy filetype:pdf will look for pages which contain the words indigenous and policy in the title and is a pdf document.

Search for a word or phrase (in quotes), but only in the body/document text.

Example: intext:"orbi vs eero vs google wifi"

Returns sites that are related to a target domain. Only works for larger domains.

Example: related:nytimes.com

Returns results where the two terms/phrases are within (X) words of each other.

Example: tesla AROUND(3) edison

Google Scholar

Google Scholar searches scholarly material on the web including; books, journal articles, conference papers and other literature from a wide range of subjects.

Use Google Scholar results as a starting point to find other relevant information on your topic by clicking:

-

'Cited by' to link to other scholarly material that cites a particular article

-

'Related articles' to link to similar articles

Evaluate and analyse the information

Evaluate the information

In selecting your materials, you need to make sure they are good sources of information on which to base your findings. To do this, you need to consider several key factors in evaluating the information such as currency, authority, objectivity and accuracy.

Analyse your sources

Once you have selected and evaluated the sources you are going to use, you need to consider in more detail how they will inform the scope and argument of your work. In other words, you need to analyse your sources in more detail:

- Does the material support your argument well?

- Or does the material contradict your argument?

- If you have any statistics or data, what aspects of your argument do they relate to, and do they help illustrate a point?

References and Attributions

Reference

Attribution

Hero image: Deep blue ocean during tide image by Alonso Photo. Licensed under a Pexels.com License